Military

In August 1914, at the outbreak of WW1, two women doctors - Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson - founded the Women's Hospital Corps (its medical staff was entirely composed of graduates from the London School of Medicine for Women) to care for wounded servicemen.

Because they anticipated a misogynistic reaction from the War Office, Drs Murray and Garrett Anderson applied to the French Red Cross, who agreed to their plan and allocated the newly built Hotel Claridge in Paris for use as a military hospital. It opened on 15th September 1914.

Despite their limited surgical experience (British teaching hospitals refused to appoint women to training posts), the hospital proved successful and the skepticism of the French and British authorities gave way to respect. The Royal Army Medical Corps (R.A.M.C.) began to treat the hospital as if it were an auxiliary to the British Army rather than the French.

Subsequently the two doctors were asked to open another hospital at Wimereux, near Boulogne. The Women's Hospital Corps (W.H.C.) ran both hospitals successfully throughout the autumn and winter of 1914.

In January 1915, following a change of policy, British casualties began to be evacuated back to England, rather than remaining to be treated in France. Drs Murray and Garrett Anderson offered the services of the W.H.C. to the British Army. The War Office had received favourable reports of the Corps' achievements and the two women were personally invited by Sir Alfred Keogh, Director General of the Army Medical Services, to run a large military hospital in central London under the auspices of the R.A.M.C. The W.H.C. closed down its hospitals in France and returned to England.

The Endell Street Military Hospital opened in May 1915 in the former St Giles workhouse, which had been previously used by the Metropolitan Asylums Board to house destitute enemy aliens and then refugees from the Continent.

The Hospital blocks were 5 storeys high, linked by a glass-covered passageway down the centre of the courtyard. The oldest part of the workhouse was dated 1727, but the children's home behind the main buildings was modern and well-built. The Hospital site also included the Guardians' offices opening on to Broad Street(now High Holborn).

To prepare the buildings for use as a hospital, extensive structural alterations had been necessary. External lifts capable of carrying stretchers had to be installed. The whole building had been cleaned and painted throughout, and electric lighting and modern cooking apparatus installed. The mortuary had contained a set of 'pigeon holes' designed to store coffins, with a gas meter taking up much of the room. Much old furniture, lumber and disused apparatus abandoned by the Guardians had to be disposed of, including the fittings of padded rooms and curious pieces of furniture used to restrain the insane. Antique baths and obsolete pipework were cast out. New ward kitchens and bathrooms were installed on each floor, and operating theatres, X-ray rooms, laboratories, dispensaries and storerooms were created.

The Hospital had 520 beds. Established to treat only male patients, it was almost entirely staffed by women - the only women's unit run by militant suffragists.

The medical staff consisted of about 15 doctors, including visiting specialists. Dr Murray was the Doctor-in-Charge, while Dr Garrett Anderson was the Chief Surgeon. However, they were known to the staff and patients as the C.O.s (Commanding Officers).

The nursing staff initially comprised a Matron (lent by the New Hospital for Women), an Assistant Matron and 28 Sisters, assisted by 60 female nursing orderlies. Other staff included a dispenser, two masseuses (belonging to the Almeric Paget Massage Corps), a Quartermaster, a Transport Officer, a Steward and other members of the Women's Hospital Corps, an unspecified number of clerks, storekeepers, cooks and cleaners and, on each floor, a male orderly. In fact, an R.A.M.C. detachment of 21 men had been assigned to the Hospital, but as most were unfit for active service, they were of relatively little use.

The Sisters' uniform was of a blue-grey washable material with scarlet shoulder straps bearing the initials W.H.C. The orderlies, who were carefully selected from the 'cultured class', wore large white overalls. There were no staff nurses, and therefore no intermediaries between the Sisters and the orderlies.

The two C.O.s were sent on a course at the Royal Army Medical College at Millbank to learn how to run a military hospital. However, the female medical staff of the Women's Hospital Corps were not commissioned and could not wear badges of rank. They were given an honorary rank, being graded as lieutenant, captain, major or lieutenant-colonel, and received the pay and allowances of their rank.

The R.A.M.C. was reluctant to take responsibility for the Hospital, convinced it would close within six months. However, because of its proximity to major railway termini, the casualties poured in via ambulance trains. At one time, some 30-50 casualties would be received, often late at night; sometimes as many as 80. Soon the number of beds had to be increased to 573.

Many new admissions had to be operated upon immediately, and the surgeons could be performing over 20 operations a day. Many patients needed major abdominal surgery, some with head injuries required craniotomy and a great proportion were orthopaedic cases with compound fractures of long bones (at one time there were 154 patients on the wards with compound fracture of the femur). As the war progressed, specialist units were established by the War Office, and patients with head injuries or femoral fractures were diverted to them. However, a large number of amputees were still admitted to the Hospital, and the staff became quite proficient at making prosthetic limbs for them. Wound infection was a major problem, and the medical staff tried different treatment regimes to improve wound healing.

Although officially a military hospital and funded by the Army, the Hospital was largely ignored by the R.A.M.C. and the Women's Hospital Corps was left to run it as it wished. Instead of the usual military practice of naming wards with letters of the alphabet (Ward A, B, C, etc.), the 17 wards were named after female saints and holy women - Anne, Barbara, Catherine, Deborah, Elizabeth, Felicitas, Genevieve, Hildegarde, Isobel, Joan of Arc, Mary, Onoria, Perpetua, Rachel, Theresa, Ursula and Veronica.

The wards were wide and bright, with windows on either side. The larger ones contained 40 beds and the smaller 30; there were also a few small wards. The walls were painted green, providing an effective background for the bed covers and screens, which differed in the various wards. The covers could be quilts in delicate colours on a light ground, or pure white, or warm red and blue striped Army blankets or salmon pink quilted coverlets. Additional luxuries (for example, standard lamps for patients to read by were provided by St Leonard's School) provided more comfort. The wards were also decorated with flowers, replaced daily by a team of volunteers led by Dr Garrett Anderson's sister-in-law, Mrs Alan Garrett Anderson, who also brightened the courtyard with a constant display of flowers in tubs and window boxes. The feminine touches gave the Hospital a warm ambience, unlike other military establishments, creating a sympathetic home-like atmosphere.

While most military and auxiliary hospitals had volunteers who arranged comforts (cigarettes, books, magazines, games) and entertainments (concerts, plays and sports) for their patients, the Hospital was ideally situated in central London and was able to call on a great number of volunteers to provide such things.

Many famous actors and actresses performed on stage in the Hospital's entertainment hall (which had the suffrage motto Deeds Not Words painted over the proscenium arch). Some 511 entertainments were arranged for the patients during the operational life of the Hospital. Sports days were also held, with crawling and cigarette races for the less ambulant. The Library was well supplied by books. Needlework classes proved popular, and regular sales of work were held, attended by Society ladies and even occasionally by members of the Royal family. At Christmas, a competition was held for the best-decorated ward.

The Hospital had a large dining-room, where convalescent patients could escape the wards and eat and socialise together.

The spacious mortuary was suitably furnished, draped with purple flags and decorated with appropriate texts.

In January 1917 Queen Alexandra visited.

Despite the expectation of the R.A.M.C. that the Hospital would close soon after it opened, it proved to be a great success. Recognition of their work resulted in Drs Murray and Garrett Anderson each being awarded the C.B.E. for war work in the newly introduced Order of the British Empire in 1917. Later, four other members of the medical staff received C.B.E.s or O.B.E.s.

In August 1917 a women's section was opened at the Hospital, with some 60 beds set aside at the top of the East Block for members of the Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps and other units. Originally intended to be only a temporary measure, the section finally closed in January 1919, by which time some 2,000 women had been admitted for surgical or medical treatment, including those who had been working abroad for the Y.M.C.A. and other canteens, as well as the wives of officers and N.C.O.s returning from the East.

In 1918 the Representation of the People Act gave the vote to women aged over 30. The Hospital staff celebrated this event by hoisting the flag of the Women's Social and Political Union (W.S.P.U.) in the Hospital courtyard.

In August 1919 the Army Council approved payment of the Army of Occupation bonus to the female doctors employed at the Hospital.

The Hospital closed in December 1919. With its three auxiliary hospitals (Byculla, Dollis Hill House and Holly Park) it had had 768 beds. During its operational lifetime, its medical staff had treated 26,000 patients (24,000 of them male) and performed over 7,000 operations.

Present

status (February 2009)

The buildings have been demolished and Dudley Court, a municipal apartment block with sheltered housing, now occupies the site.

The site of the former Hospital in Endell Street is located behind the Oasis Sports Centre on High Holborn.

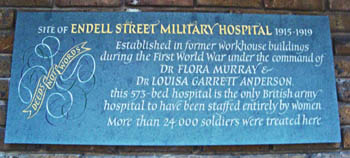

In November 2008 a grey plaque was unveiled on the wall of Dudley Court to commemorate the Hospital.

The commemorative plaque.

(Author unstated) 1917 Care of the wounded. British Journal of Nursing, 27th January, 61.

(Author unstated) 1917 League of St Bartholomew's Nurses. British Journal of Nursing, 27th January, 66-67.

(Author unstated) 1917 List of the various hospitals treating military cases in the United Kingdom. London, H.M.S.O.

(Author unstated) 1919 The Service. British Medical Journal 2 (3070), 582.

Geddes JF 2006 The Women's Hospital Corps: forgotten surgeons of the First World War. Journal of Medical Biography 14, 09-117.

Geddes JF 2007 Deeds and words in the suffrage military hospital in Endell Street. Medical History 51, 79-98.

Geddes JF 2008 The Women's Hospital Corps and the Endell Street Military Hospital. Camden History Review 32, 13-18.

Geddes JF 2010 Medicine with a mission: the suffragette military hospital in Covent Garden.

Leneman L 1993 Medical women in the first world war - ranking nowhere. British Medical Journal 307, 1592-1594.

http://1914-1918.invisionzone.com

http://textline.wordpress.com

www.1914-1918.net (1)

www.1914-1918.net (2)

www.flickr.com

www.iwm.org.uk (1)

www.iwm.org.uk (2)

www.londonremembers.com

www.nationalarchives.gov.uk

www.plaquesoflondon.co.uk

www.prints-online.com

www.scarletfinders.co.uk

www.wellcomecollection.org

Return to home page